Lunar New Year, the Cantonese Way

Lunar New Year is the most important holiday in Chinese culture. Historically tied to agricultural cycles, it marks a rare pause in the calendar when families reunite, rest, and look ahead with hope for a prosperous year ahead – expressed through ritual, food, and shared tradition.

More than a celebration, Lunar New Year is a period shaped by ancient beliefs and everyday practices passed down through generations. While it is observed across the Chinese world, customs vary by region, village, and even family, making the experience deeply personal.

Also known as Chinese New Year, the festival follows the traditional lunisolar calendar, marking the beginning of a new year and the symbolic arrival of spring. Celebrations typically last 15 days, beginning on New Year’s Eve and concluding with the Lantern Festival (元宵節).

The New Year represents a moment of transition, closing one chapter and welcoming another with care and intention. Preparation for the New Year reflects a collective desire to begin with a clean slate – emotionally, materially, and spiritually.

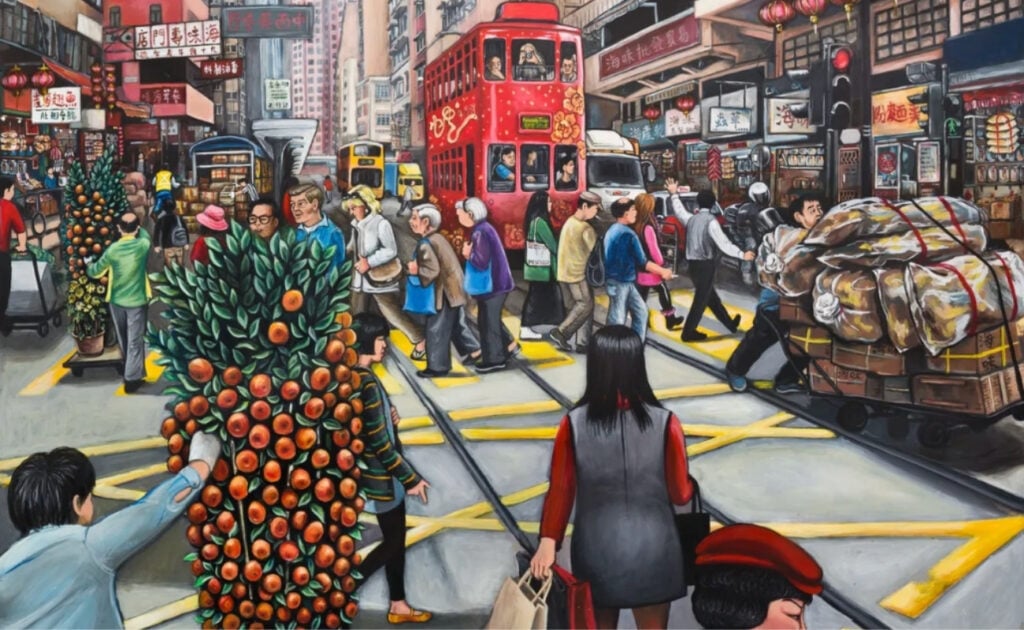

In Cantonese households, red decorations such as fai chun (揮春), or auspicious banners, are hung on doorways around the home, while the character fuk (福), meaning fortune, is often displayed upside down for the luck to be poured into your home (福倒/福到).

Potted mandarin trees are commonly placed at entrances or in living spaces, as the Cantonese word for tangerine (“kat” 桔) sounds like “luck,” making them a symbol of prosperity and abundance. Alongside these, blooming plants such as peach blossoms or pussy willows are used to represent growth, vitality, and new beginnings for the year ahead.

New Year’s Eve

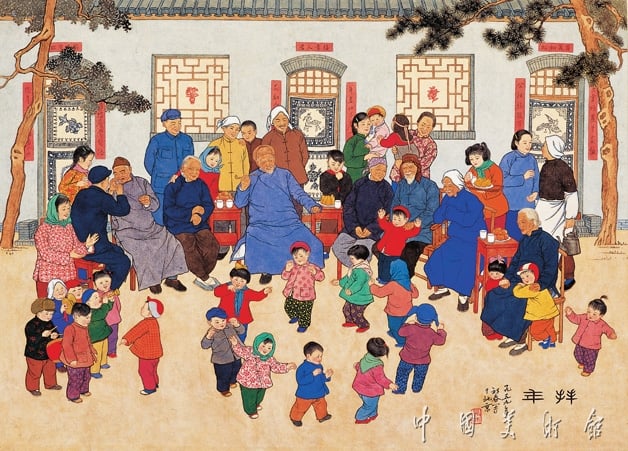

At the centre of Chinese New Year is the act of returning home. No matter how far one has travelled or how busy life has become, New Year is a time to reunite with family. The festivities start on New Year’s Eve with the family reunion dinner, the most important meal of the year. Every dish served carries meaning, often drawn from Cantonese wordplay – and is meant to channel auspiciousness.

The New Year’s Eve meal will feature poon choi (盆菜), a layered casserole filled with meats, seafood, and vegetables, symbolising abundance and unity.

A whole fish is always present, as yu (魚) sounds like “surplus,” representing prosperity. “Fat choi” (髮菜), a dried desert moss whose name sounds like “becoming wealthy,” is often paired with dried oysters (“ho si “ 蠔豉), which sounds like a Cantonese homophone for “good business.” Together, the dish fat choi ho si (發菜蠔豉) forms an auspicious phrase symbolising prosperity and success – allowing families to quite literally eat their wishes for the year ahead!

Among Cantonese traditions, another ritual is bathing with pomelo leaves on New Year’s Eve. Known as luk yau ip (碌柚葉), this practice involves washing the body with pomelo leaves, believed to cleanse away bad luck and negative energy from the past year.

New Year’s Day

New Year’s Day and the following first days are devoted to “bai nin” (拜年), the tradition of visiting families and friends to exchange greetings and blessings. Elders are visited first, reinforcing respect and hierarchy within the family. These visits are filled with well-wishes for health, success, and prosperity, setting the tone for the year to come.

One of the most recognisable New Year customs is the giving of “lai see” (利事), or red packets usually adorned with the family surname or zodiac of the year. Traditionally given by married individuals, elders, and employers, lai see symbolises blessings, protection, and good fortune. Rooted in the traditional belief of warding off evil spirits, the act of giving lai see serves as a gesture of goodwill.

When friends and family visit during the New Year, it is customary to serve foods associated with luck and auspicious meaning. A staple in Cantonese households is the chuen hap (全盒), or “togetherness box,” filled with small sweet treats symbolising unity, harmony, and prosperity. Traditional festive foods such as sticky rice cake (“neen go” 年糕) and sweet glutinous rice balls (“tong yuen” 湯圓) are commonly eaten on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day. Neen go symbolises progress and improvement year after year, often associated with career advancement, financial growth, and academic success. Tong yuen, whose name echoes the word “tuanyuan” (reunion), represents family unity and togetherness.

On New Year’s Day itself, hair washing is typically avoided. In Cantonese, the word for hair (“fat” or 髮 ) shares the same character and pronunciation as fat in fat choi meaning to become wealthy. Washing one’s hair is therefore believed to wash away your good fortune.

Wearing new clothing for Chinese New Year is a symbolic gesture of renewal and fresh beginnings. Red garments are particularly favoured (even down to the underwear!), as the colour is traditionally associated with luck and positive energy. New shoes or slippers, however, are purchased before the start of the New Year, as buying them during the festive period is avoided. In Cantonese, the word for shoes, “haai” (鞋), phonetically similar to a sigh and is believed to suggest an unlucky beginning to the year.

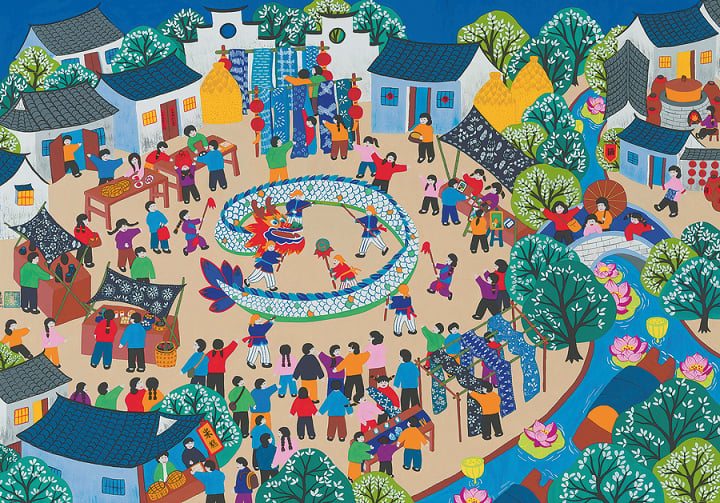

In the days following the New Year, families often visit temples or gather to watch dragon and lion dance performances, continuing the celebrations through shared rituals and time spent together. The pace of these days is intentionally slower, creating space to reconnect, rest, and ease into the year ahead.

While some of these customs may seem symbolic or old-fashioned, they remain meaningful expressions of care, intention, and continuity. Chinese New Year traditions are not fixed rules but living practices that have been adapted over time, shaped and sustained through family memory. At the core, these traditions remind us that how we begin matters, that good fortune is nurtured through thoughtfulness, and that renewal often starts at home.