- This event has passed.

Siah Armajani and Rasheed Araeen: Two Manifestos

2 April 2022 - 14 May 2022

FreeEVENT DESCRIPTION

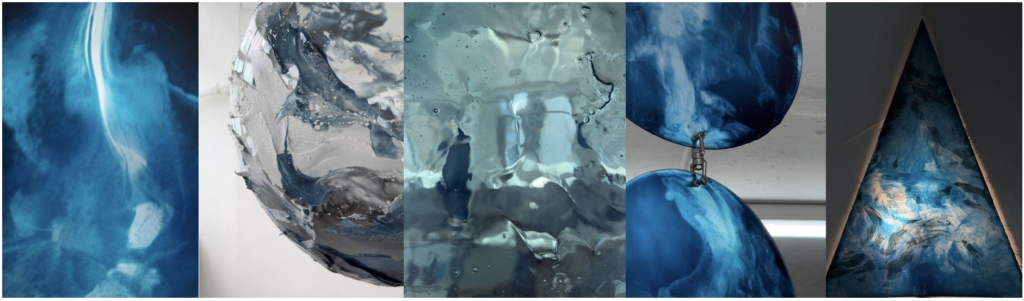

Siah Armajani and Rasheed Araeen – two diaspora artists who both migrated to the West – invented their own unique responses to the ingrained socio-political phenomenon of their respective societies through art. Opening on 2 April at Rossi & Rossi Wong Chuk Hang, Two Manifestos features works by these artists from the 1970s that mirror their individual experiences in cultures foreign to them. The exhibition also covers more recent works that show the synthesis of the art language each one developed.

Seven years upon his arrival in the United States, Iranian artist Armajani (1939–2020) officially became an American citizen. To secure the sense of belonging to this new identity, he created Land Deeds (1970), a folder containing signed deeds to the one square inch of land he had purchased in each of the fifty states on 16 March 1970. As Clare Davies, assistant curator of modern and contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, points out in the 2018 exhibition catalogue Siah Armajani: Follow This Line, Armajani saw the ‘United States through the wrong end of a telescope, playing the role of the eager immigrant and acquiring land in not one but all fifty states’.

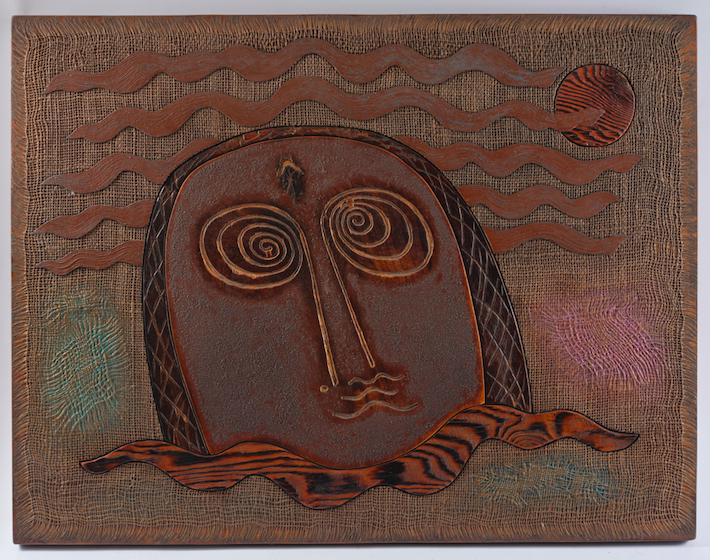

Similar sentiments of disillusionment can be found in the early works of Karachi-born Araeen (b. 1935). After arriving in London in 1964, the artist worked as a draughtsman and civil engineer to support his art-making practice in the studio he rented on St Katherine Docks. The One That Could Not Float Away (1970) documented a performance he enacted on the dock: he threw painted wooden disks into the water, and the disks that were stuck and unable to drift along the Thames represented the artist’s own diasporic nature. The implication of displacement and sense of alienation is even more pronounced in the photographic series Christmas Day (1979), for which the artist took photos of himself alone at the London underground on 25 December 1979.

Both Armajani and Araeen eventually moved on from looking back on their own experiences to realising their own art languages. Exemplified by Four Bridges (1974–75), the bridge was a central motif for Armajani. The artist once noted, ‘During the mid-sixties, I, as well as other artists, was searching for a new form of content. I turned to the social sciences as a model for a compatible methodology that would incorporate political, social and economic considerations’. To the artist, these considerations were projected into functions of the architecture, and the dissection of these forms would reveal much of the socio-historical context.

Whilst the bridge is central to Armajani’s art language, the cross – or, more specifically, the cruciform – is the means Araeen incorporates to lay bare his many internal conflicts and concerns. Through an investigation of industrial ‘structures’ during the 1960s, he developed the shape of a cross at the centre of a nine-panel grid system. In Cruciform series and Jouissance (1987–94), the centred images and the surrounding images dynamically interact on the themes of modernism.

The diaspora experience inspired these artists to reflect on the established norms and traditions ingrained in their newly adopted countries, in addition to their contemporaneous concerns regarding the ever-changing social, political and cultural realities of these places. Two Manifestos, to a certain extent, reviews this trajectory; it also presents the honed, idiosyncratic expressions of both artists that continue to resonate today.

Details

- Start:

- 2 April 2022

- End:

- 14 May 2022

- Admission:

- Free

- Event Category:

- Multimedia, Photography